Updated: July 21, 2020

Introduction

Since 2019, the Center for the New Middle Class has been surveying prime and non-prime households on a variety of financial health and sentiment indicators, offering a unique look into the lives of the 150 million Americans with credit scores below 700.

June showed a significant weakness in American households, especially those who currently have prime credit. That would suggest that there is a meaningful number of households who will begin to slide out of prime into non-prime status as their finances deteriorate. This deterioration will come in the form of job loss, pressure from medical bills, and a creeping debt load.

Non-prime respondents are not showing a corresponding erosion. While it would be untrue to say they are faring better than prime, it is fair to say that they are faring better relative to their status prior to the COVID economic crisis.

Perhaps the most notable place to see these trends play out is in household debt. The percentage of households in debt is dropping even as the number of prime households who carry different forms of debt is increasing. This suggests a bifurcation of the market, where some are doing better and others are doing worse.

Job Stability

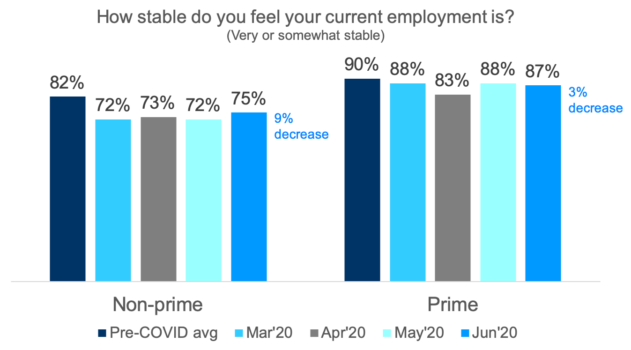

One of the most interesting insights from the non-prime tracker has been the idea that even when the economy was strong, a significant number of people felt their employment was unstable. As the economy’s future is more uncertain than ever, that percentage has grown, but maybe not as much as you would expect.

At the monthly level, prime consumers’ confidence that their employment was stable held high through June and non-prime consumers’ confidence continues to strengthen. However, the story appears to be shifting as we look at the weekly data.

Even more surprising, the sense of job stability has actually improved for non-prime respondents in June and now stands at a post-COVID high. Prime respondents maintained fairly high confidence which has shown significant erosion over the last couple of weeks. It is possible that they are anticipating a second-wave unemployment event if the economy fails to bounce back.

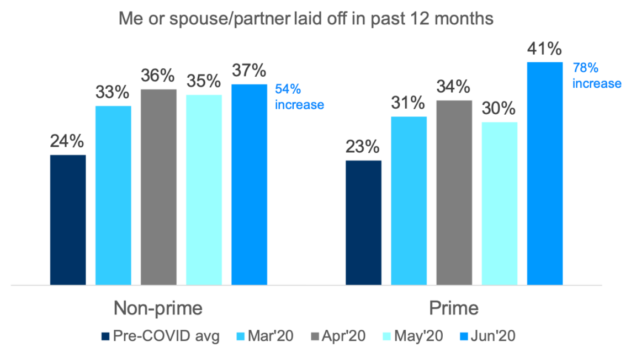

The job security that does exist flies in the face of the fact that a meaningful percentage of American households have experienced a job loss. So, while the country’s unemployment for June came in officially at 11.1%, the non-prime tracker shows just how many households have been affected by job loss in the prior 12 months.

The households affected continue unabated. Once again, prime households might be the most surprising finding as June saw a significant increase and showing a higher percentage than non-prime households.

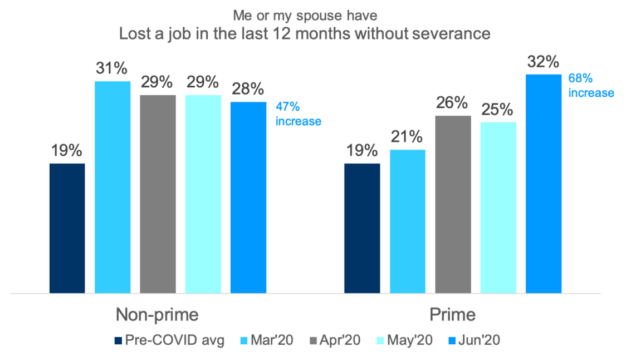

A third of the jobs non-prime households lost did not come with company-provided severance packages, which increased the fragility of those households and shortened the runway they had before landing a new job.

While severance-free job loss was less rare for prime households, that trend appears to be changing and they experienced a significant jump in June.

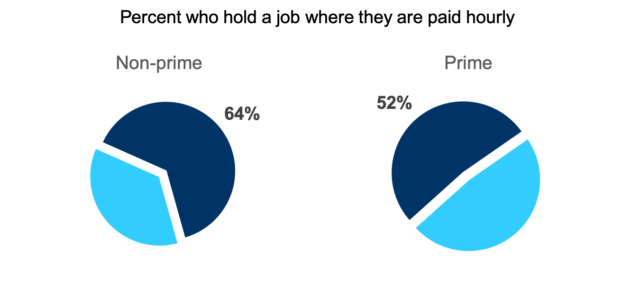

Early in the pandemic, evidence for the increased fragility of non-prime households could be explained by the different types of employment that they hold. The fact that two-thirds of non-prime households are paid hourly could explain lower severance, less job security, and higher employment volatility.

Increased employment insecurity amongst prime respondents may suggest that the economy’s deterioration has begun to cut deeply into white-collar and salaried jobs.

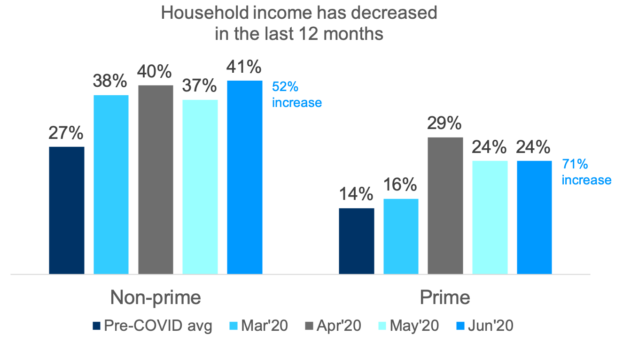

We continue to see an increase in the number of households who report that their year-over-year income has decreased, especially amongst the non-prime. While this can certainly be a function of job loss, it might also be indicative of those who are wage earners: companies may be cutting back hours before they lay off workers.

Day-to-Day Expenses

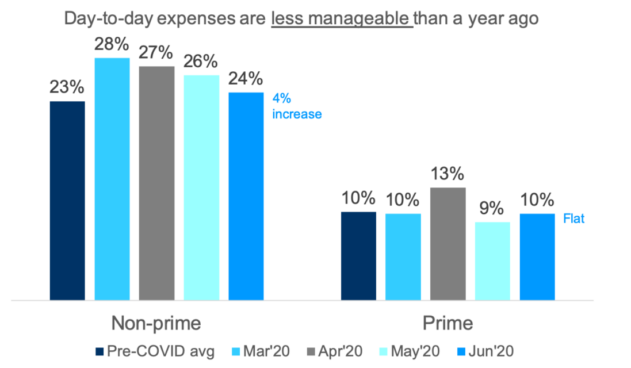

The manageability of day-to-day expenses is one of the key factors that can strain household finances. This pressure is often the Trojan Horse of household finances. A single month of unmanageable expenses can feel common which means that the expenses a crisis can cause often sneak up on a family, and multiple months of unusually high expenses can destabilize an already tenuous equilibrium.

The COVID crisis created an unusual situation where shelter-in-place orders actually artificially decreased household expenses. Even as the economy puts income pressure on many households, they are not feeling a corresponding expense pressure.

While non-prime households felt that pinch at the outset of COVID, households have improved their ability to cope month-over-month, with June falling in line with pre-COVID averages.

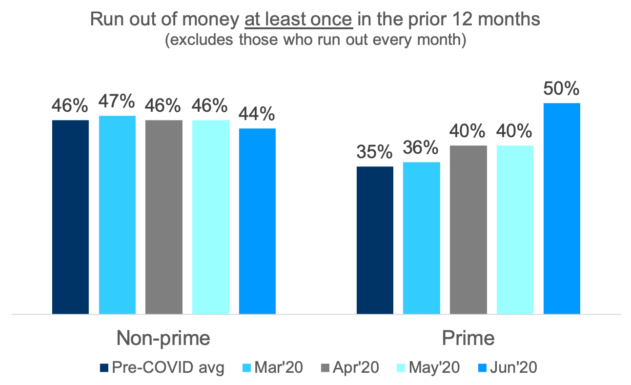

Throughout the COVID economic crisis, there has not been an increase in non-prime households who say that they have run out of money at least once in the prior 12 months. What is much more surprising is the steady increase through May in prime households who were running out of money and then the much more dramatic increase in June.

Running Out of Funds

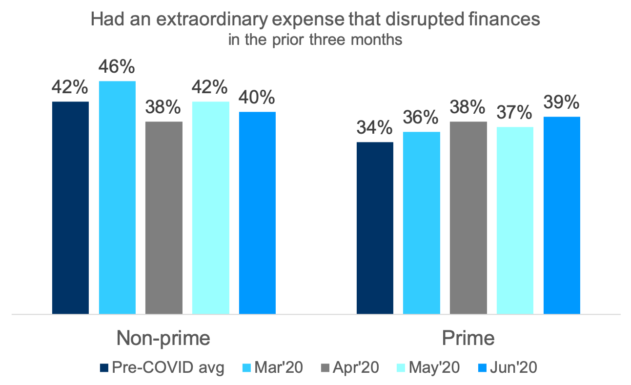

In a normal economy, it is the extraordinary expenses rather than day-to-day expenses that can cause the most disruption to household finances. The surprise of extraordinary expenses has been on the rise amongst prime respondents with almost 4 in 10 households reporting one in the prior three months.

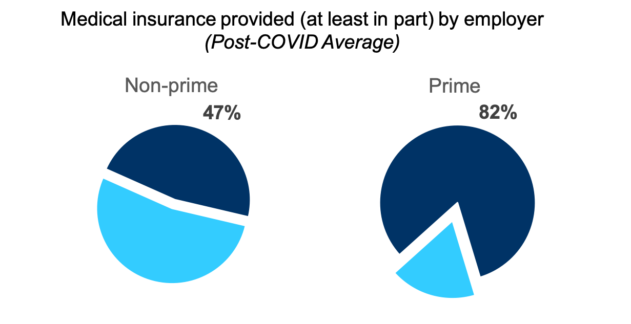

One of the most destabilizing events in household finances are medical expenses. While previous research at the Center for the New Middle Class has shown that medical expenses can even disrupt households with health insurance, the sudden and dramatic employment disruption due to COVID is likely to spawn a medical expense crisis as more households who rely on medical coverage from their employers lose both their income and their health insurance.

This will be felt most acutely by prime Americans. This double-whammy will almost certainly be the impetus that will push more people out of prime credit status into the ranks of the non-prime.

With decreased savings rates, increased cost of living, and stagnating incomes, credit has become the necessary tool for most households to overcome minor financial setbacks. Short-term lending helps households smooth over fluctuating expenses and uneven income.

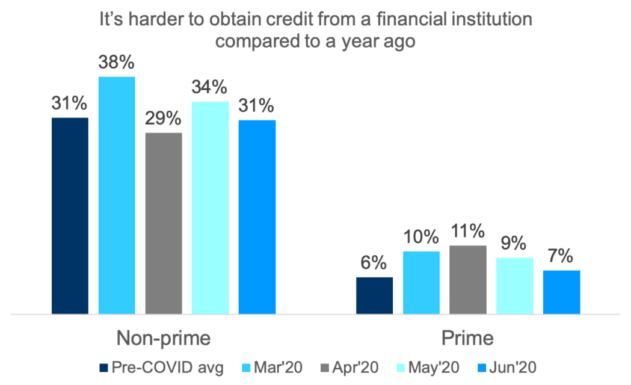

One of the most predictable consequences of the onset of a recession is the increased caution of lending institutions. They often pull back the credit they offer while they shore up their own balance sheets or allow the dust to settle, so they can be sure they are assessing lending risk appropriately.

Unsurprisingly, non-prime households always have a harder time obtaining credit. The preceding graph, however, does not indicate the percent of households who can’t get credit, but rather the percent of households who feel like it is harder to obtain credit than it was a year ago. This is meant to help determine whether people feel the pinch of constrained credit.

So far, the COVID recession has not caused households to feel like their credit options are more constrained compared to the booming economy of 2019. Knowing that most credit institutions did indeed pull back on their offers of credit, it will be interesting to see when that reality reflects on people’s attitudes.

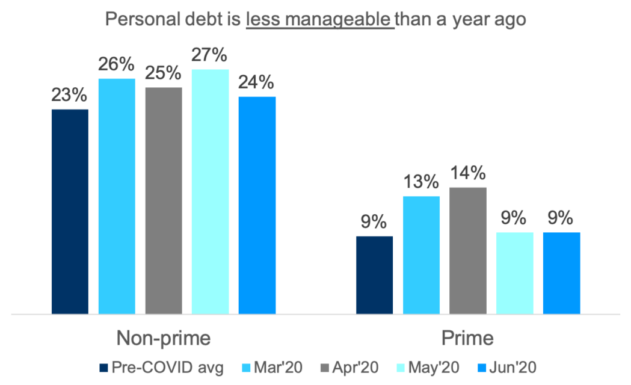

Policymakers fear a recession leads to existing or new debt crushing families and limiting their flexibility, which can further dampen a wider economic recovery. While prime households felt the impact of their debt through March and April, they are back to pre-COVID levels. Though the number of non-prime households who feel their personal debt is less manageable slightly increased during COVID, that feeling has now stabilized and was consistently less volatile than prime households.

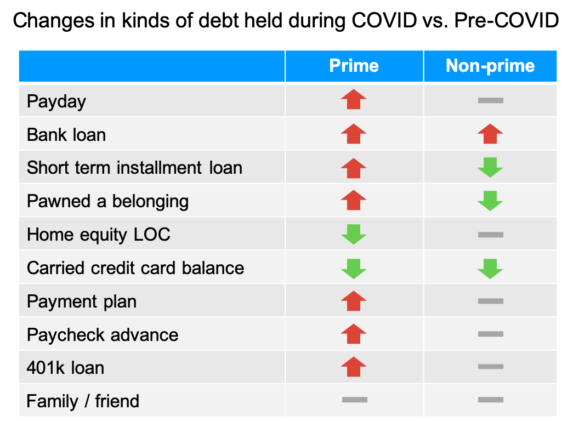

Perhaps the most surprising finding from the tracker has been in tracking the types of debt households are carrying. When asked which types of debt they currently carry, we found that fewer (or the same percentage of) non-prime households reported using every debt type after COVID as compared to before COVID. Compared to before COVID, more prime households now report holding payday loans, bank loans, short-term installment loans, pawning an object, utilizing a payment plan or paycheck advance, and taking a loan against their 401k retirement investment.

Household Debt

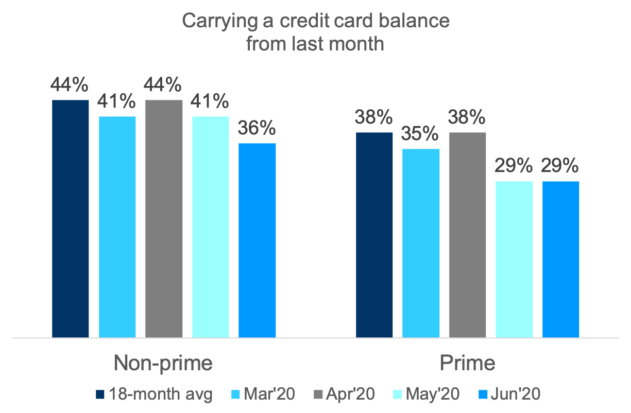

The slide in the percentage of households who claim to be carrying credit card debt continues for the fourth month in a row. Credit cards, of course, represent the most liquid form of short-term borrowing and could be considered a leading indicator to whether household finances are better or worse off from a month-to-month basis.

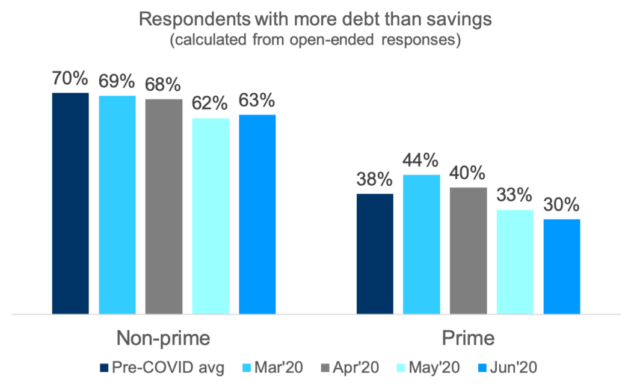

We are seeing a decrease in the percentage of households who report holding more consumer debt than they have in savings.

There are likely several reasons for this decrease. One of the more likely reasons is that government stimulus checks shored up the finances of even the 60% of households that were unaffected by the economic slowdown. Those households likely used those funds to lower the personal debt they were carrying.

Another possible reason is that normal household expenses had dropped. Shelter-in-place orders meant fewer trips to the gas station, fewer nights out, etc. It is likely that these households re-purposed the money they would have spent on expenses toward their household debt.

Stimulus Checks

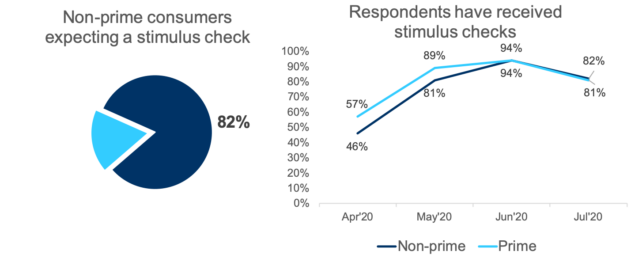

A little over 4 in 5 non-prime Americans expected to receive a government stimulus check. A vast majority of those checks were delivered by May.

One of the indicators of whether the stimulus check was needed for households can be found in how people said that they would use the funds. Almost half of prime respondents said that at least some of those funds would be placed into savings.

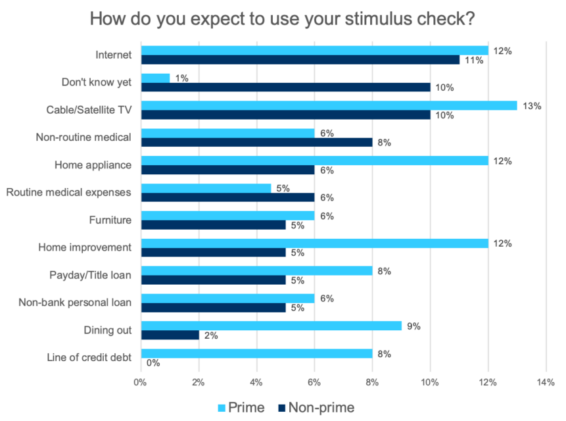

Non-prime households were more likely to earmark those funds for groceries, housing, utilities; in other words, day-to-day needs.

Furthermore, prime households were far more likely to expect to use their funds for discretionary spending like home appliances, home improvements, and even dining out.

Characteristically, non-prime respondents were far more likely to admit that they don’t know yet how they will use the funds. These households don’t count their chickens before they hatch and tend to make do with the resources at hand.

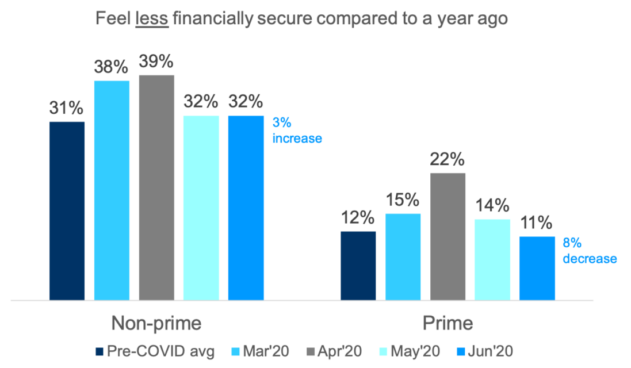

Perhaps surprisingly, while there was a spike in March and April, in June there was no increase in the number of respondents who say that they feel less financially secure than they did a year ago.

As a non-COVID-related insight, it is telling that a third of non-prime consumers during a time when the economy was strong felt that they were less financially secure than they were during the prior year. It is perhaps telling that they do not feel more vulnerable than they have in the past, suggesting that economic boom times are not egalitarian.

Financial Security Versus One Year Ago

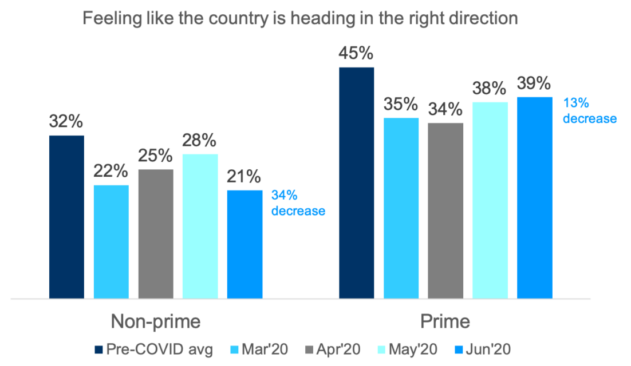

Given the economic and health uncertainty that dominates the news cycle, it is not surprising that reported confidence that the country is going in the right direction has dropped.

What might be surprising is that even during times of economic strength, less than half of respondents thought that the country was heading in the right direction.